I am a first generation Canadian visual artist and musician currently living in Toronto, which is located on the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples.

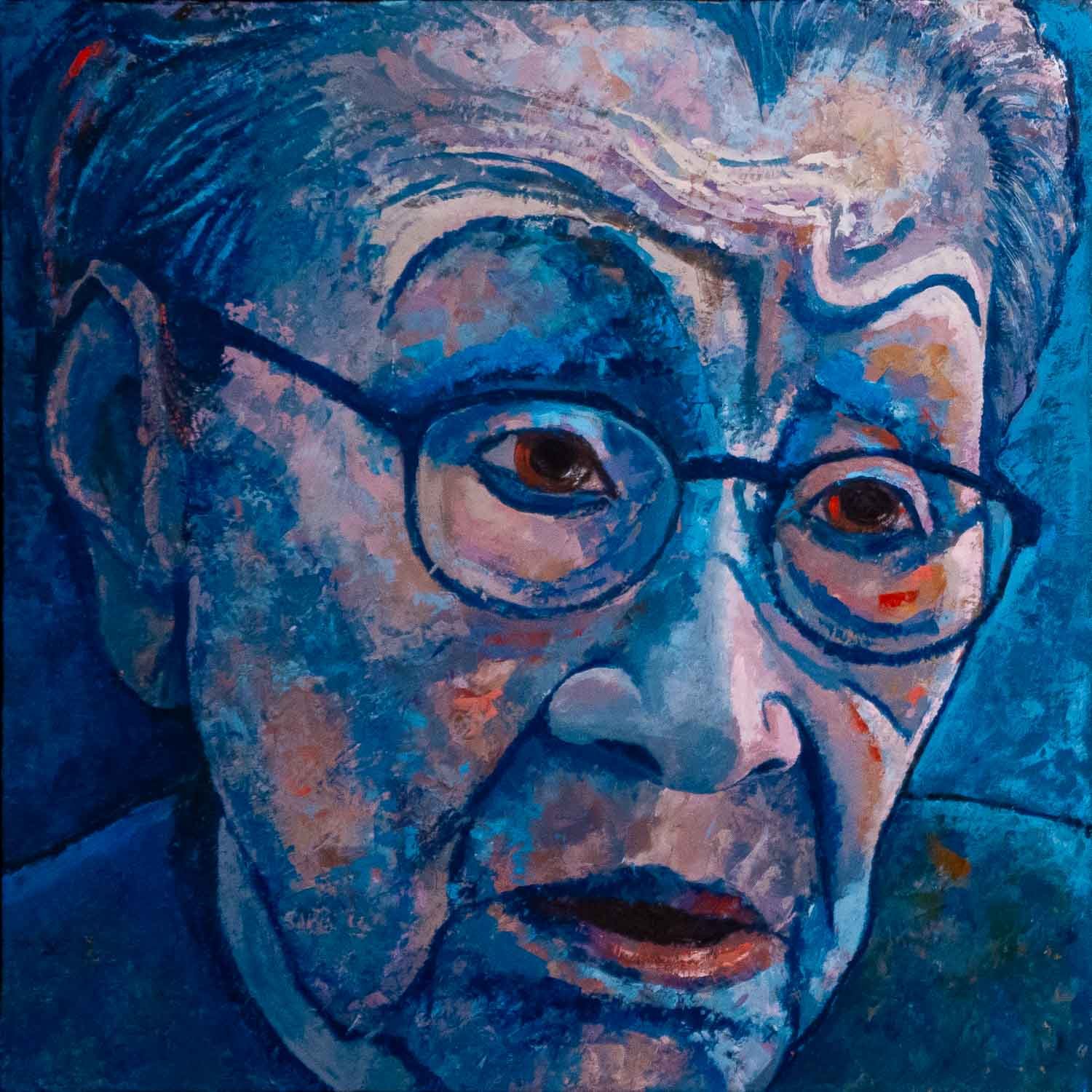

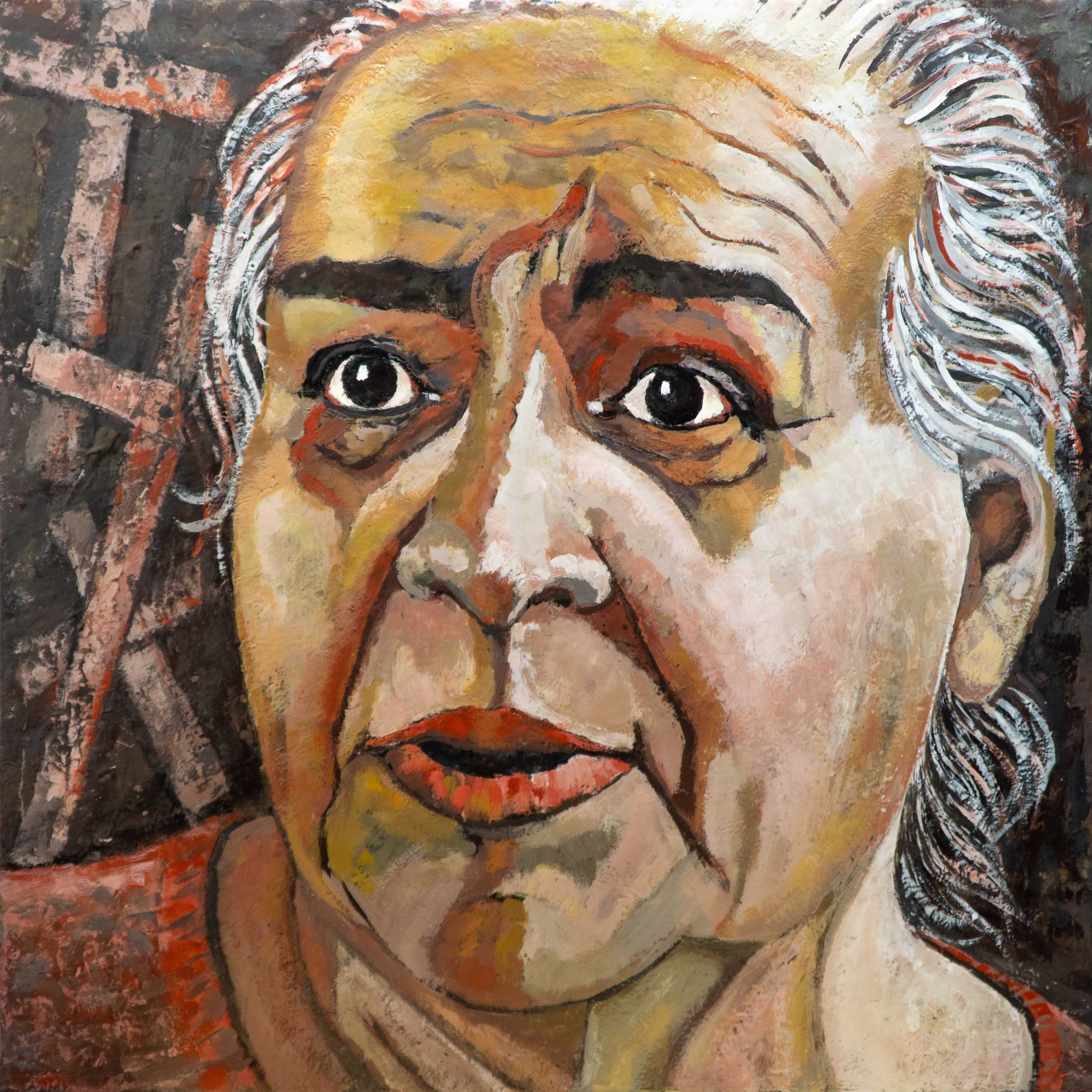

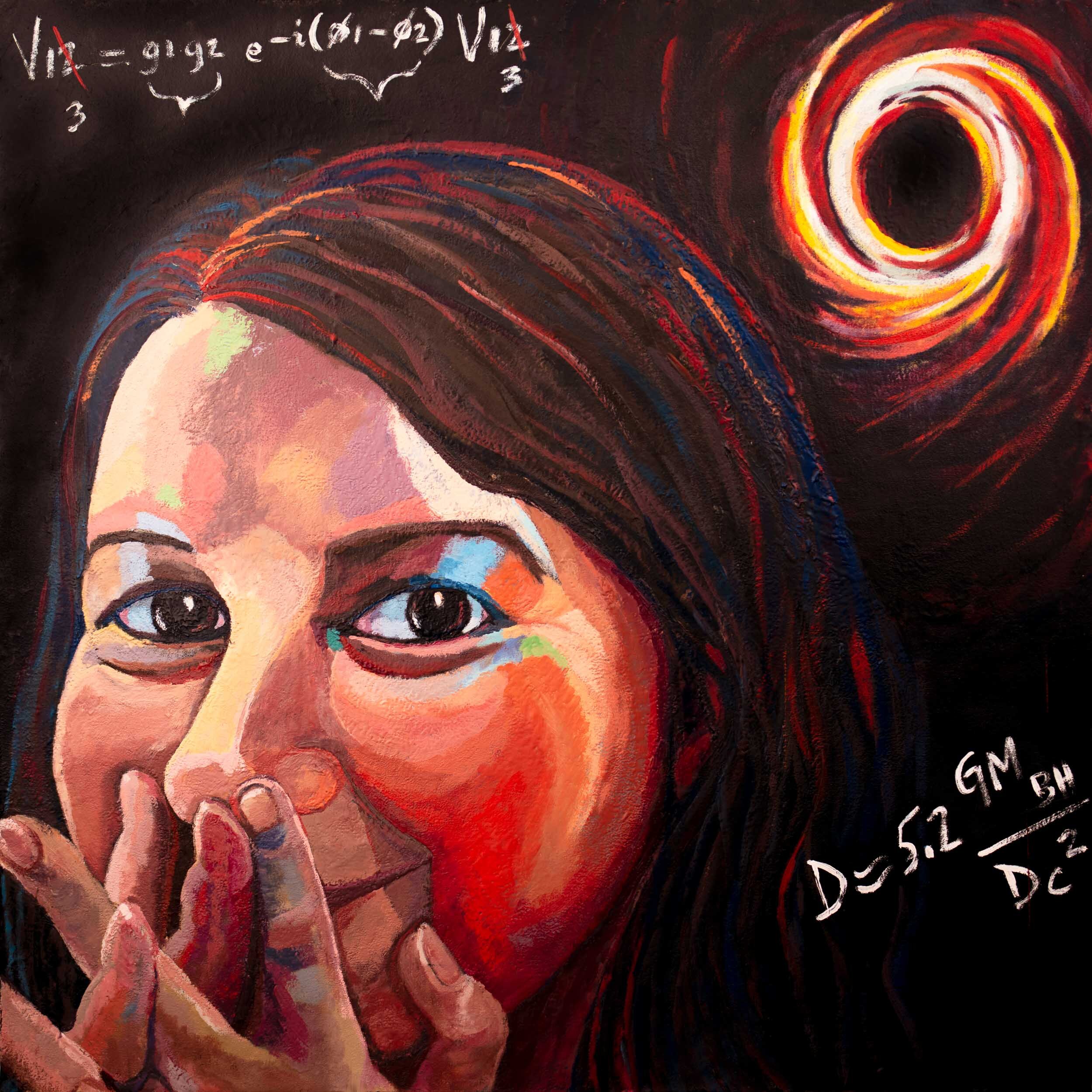

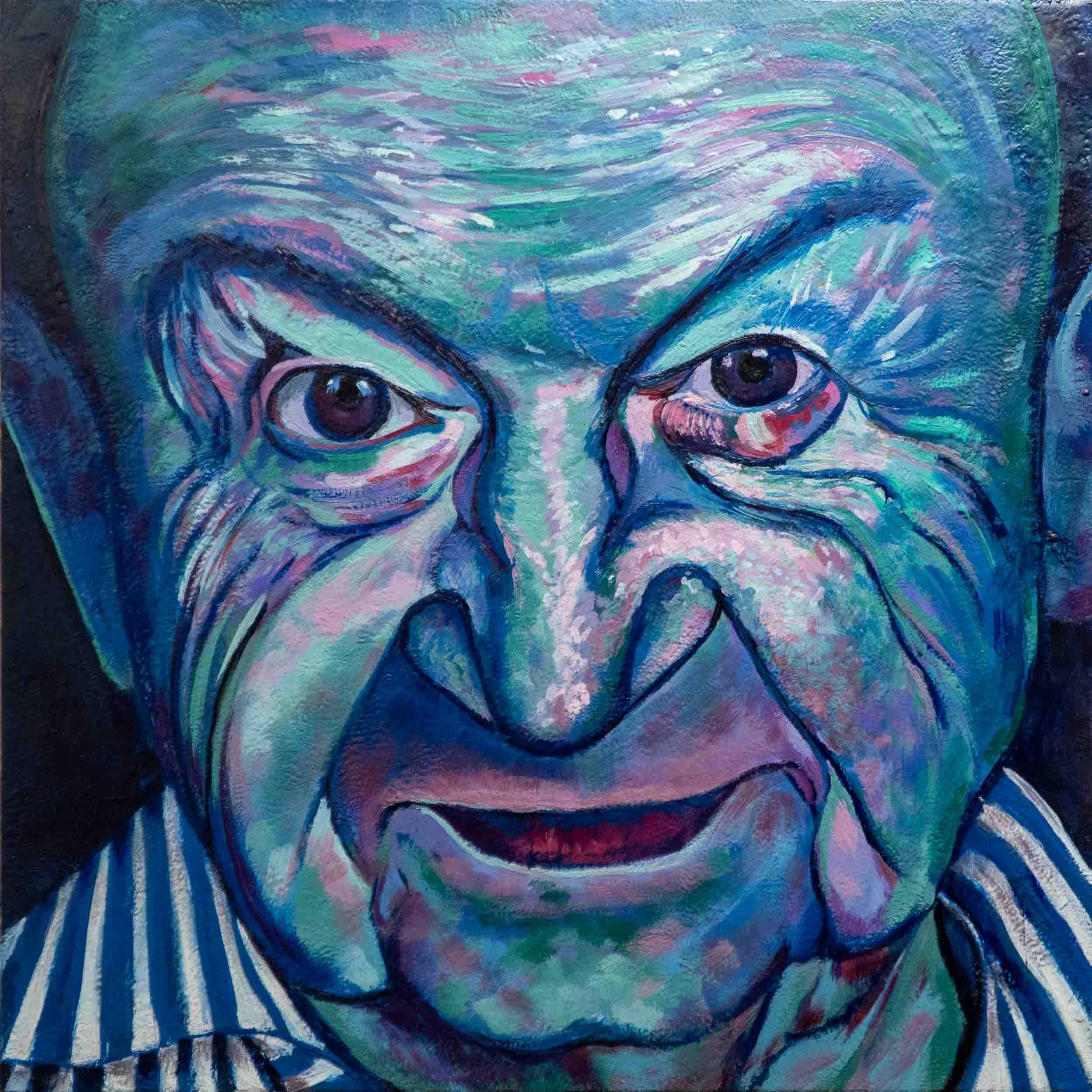

Currently I am developing an interactive art installation and social engagement project entitled — Eyeing Medusa — encompassing a series of encaustic paintings, interactive art installations, workshops and digital media resources.

Intended as a catalyst for change — Eyeing Medusa is inspired by wise/willful women making a difference in the world today; and explores how historical representations of women in art relate to problems in contemporary society.

Eyeing Medusa offers a response to the plethora of paintings, sculptures, plays, stories and operas in the Western world in which historically women are either idealized and objectified; or vilified, victimized and blamed; and in which women of colour are either hyper-sexualized, servants or notably absent.

Eyeing Medusa invites viewers to look at women in a new light.

It has been remarked upon that I address a lot of social issues through my work. Recently I was asked how I — as a self-identified settler person — have come to engage with these issues as an Artist.

I think that’s a good question.

In answer, to quote the story of the scorpion and the frog, I’d have to say — “because it is my nature”.

I’ve always been outraged by and fought against injustice, sexism and racism — even as a little kid.

I was raised with an appreciation for all world religions and philosophies; a poster with the words “Black is Beautiful” on the living room wall; and a belief in the concept “Unity in Diversity” which was carved on my grandfather’s headstone. My ancestors were human rights activists during both world wars. Some of them perished in the concentration camps. I have the blood of so many different nationalities in my veins that I joke that in my family whenever someone wanted to get pregnant they jumped a border. Be that as it may, my mother always told me — “If you want to have a friend, you have to be a friend” — so that’s what I’m doing — in the best way I know how.

I seem to graduate towards whatever other people aren’t doing; looking at things other people aren’t seeing. All my life people have called me out as “different” — and I’ve had a few grisly experiences which I won’t go into here but suffice it to say — all of it provoked me to identify with people who are perceived as “others”.

I have a particular soft spot for First Nations issues because the first place I found real friendship was within their communities. You never forget love and kindness. And when your friends tell you about their experiences in foster homes or prison or residential school; or tell you about the effects of mercury poisoning in the water or black mould in their houses and talk about the children in their communities committing suicide — it’s all very real and relevant and personal.

So yeah, I care. Deeply.

And being me — when I realize that the majority of people don’t seem to care or be thinking about this — that’s when I get triggered and have to do something.

And when for the umpteenth time I’m in a car with one of my Black friends driving and we get pulled over by aggressive and scary cops when we’ve been doing absolutely nothing wrong — while the previous day my father has sailed blithely through a red light saying “wheeee” and they just smile and basically wave him on — yeah I see privilege and racism and it makes me mad.

Personally, I don’t have to worry about myself or my children being slaughtered in the street for wearing a hoodie or going for a run; or shot for sleeping in a car because of the colour of my skin. But my friends do. So that’s why one of the first portraits I painted in my project Eyeing Medusa was inspired by Patrisse Cullors who started the movement Black Lives Matter.

Everything comes full circle it seems . . . One never knows when the seeds are being sown — precisely what will germinate or when!

My early works (SpiderWoman, Virago Project) centred around ancient mythology, contemporary archaeology, and archetypal images of the Goddess — while I sought to understand traditional female roles, expectations and identity.

Later, with my works Dragon Tango and then Arising Phoenix — exploring global but weirdly binary interpretations of the symbol of the dragon — I found myself wondering how the winged fire-breathing Western dragon came to be thought of as female: an evil, smelly, slimy, solitary cave dwelling hoarder of treasure and destroyer of crops and livestock; whereas the Eastern Dragon was thought of as male: wise and elegant, with a phoenix as consort, known for climbing the clouds (in the absence of wings) and reaching great heights.

I was living in Japan during one of two Artist Residencies, when I first heard the expression — “Be a dragon and the clouds will come” — as encouragement for aspiring to greatness.

Having grown up in the West with — “she’s a dragon” — as a pejorative term, this completely different interpretation really intrigued me.

My project Parallel Lines was inspired by the memory of a story that haunted me for years.

Jimmy, a young Cree man who I met at an Elder’s Conference in Curve Lake, told me that by age sixteen he had lived in fourteen foster homes. One day, convinced that no one loved him, he was so depressed that he threw a shovel through a jeweller’s window, figuring that at least he’d be wanted in jail. When I met him he was in the process of rebuilding his life, recovering from substance abuse and the trauma of life in prison.

Years later — during an artist residency where I was creating sculptures from discarded materials reclaimed from government buildings — Correctional Services Canada offered me prison beds from the former Kingston Penitentiary for Women.

At the time I was coming to the end of an unhappy marriage feeling imprisoned by my own life choices. When Correctional Service of Canada asked if I might be able to do anything with prison beds — for some reason I immediately thought of Jimmy and how both of us had effectively imprisoned ourselves through our beliefs and choices.

So I created the installation “15 Minutes of Fame” featuring a prison bed and a standard issue get-out-of-jail prison suitcase filled with objects with which Visitors could interact to share their own stories. This was the work that kicked off my interactive art installation and social engagement project: Parallel Lines.

“This was the safest place in prison”

Encompassing encaustic paintings, interactive sculpture installations and workshops, Parallel Lines is a very interesting and successful project because it inspires people of all ages, and social, economic and cultural backgrounds to interact with the artworks and share stories.

That, to me, is what matters.

Anything that brings us closer to understanding each other and appreciating our varied viewpoints and ideas — that’s what lights my fire.

The odd thing about Parallel Lines is that although all the paintings in the series feature a solitary female figure — recognizably myself — I have never felt the work to be specifically about me. And neither have the visitors. Everyone sees his or herself in the work. I feel honoured that visitors are so eager to share their stories and connect with me and other viewers.

Over the course of numerous exhibitions I’ve realized that I can (and do) share my stories too — and this is part of what led to Eyeing Medusa.

I’ll have to tell you about that in another article.

Thanks for reading!

Be well, be safe and be kind.

cheers — Amanta

Amanta Scott, encaustic on canvas on cradled panel, Eyeing Medusa series, 36 x 36 in/92 x 92 cm, 2019. Read more