Georges Seurat, 1882-83, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By gift

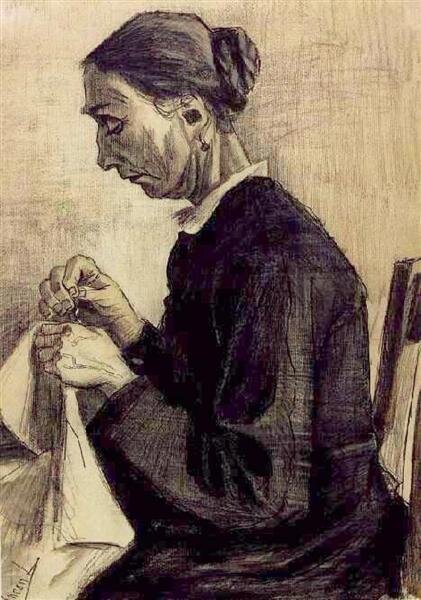

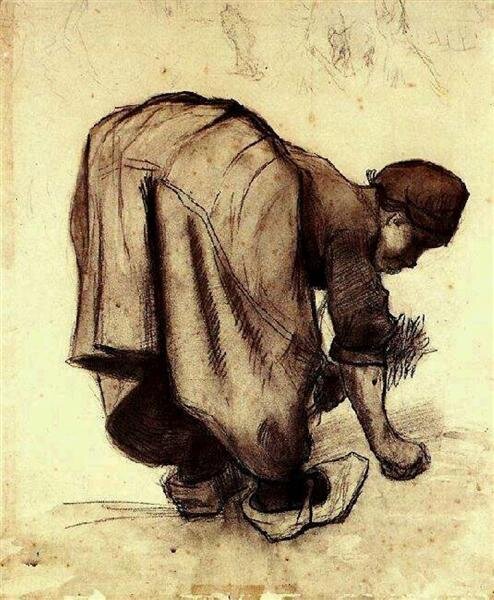

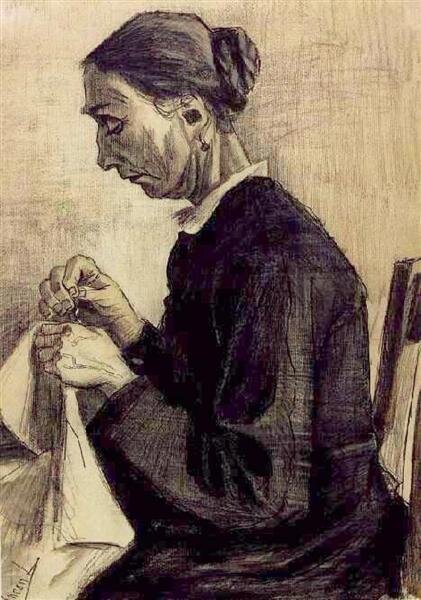

Vincent van Gogh, 1885; Nuenen, Netherlands: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

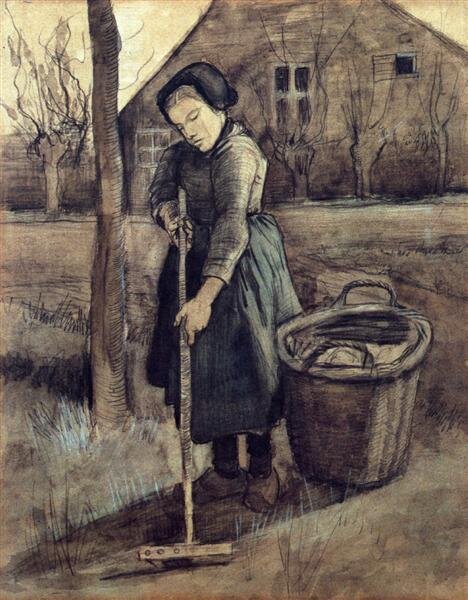

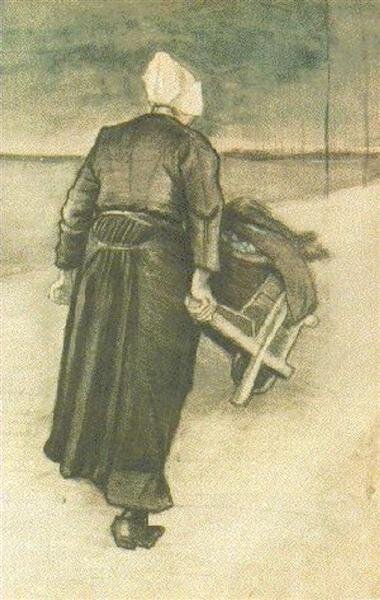

Vincent van Gogh, 1883; The Hague, Netherlands: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

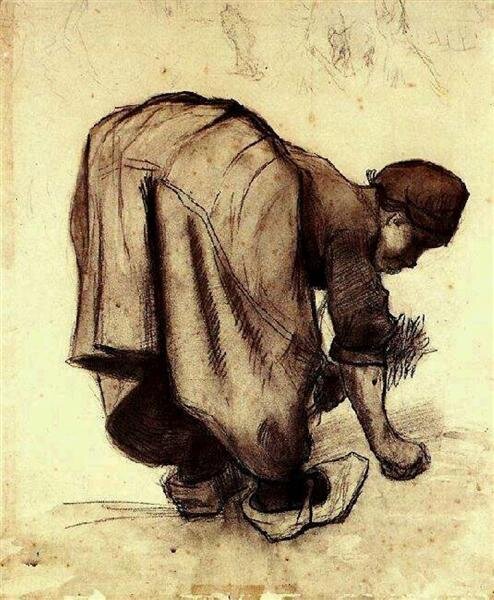

Vincent van Gogh, 1883; The Hague, Netherlands: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

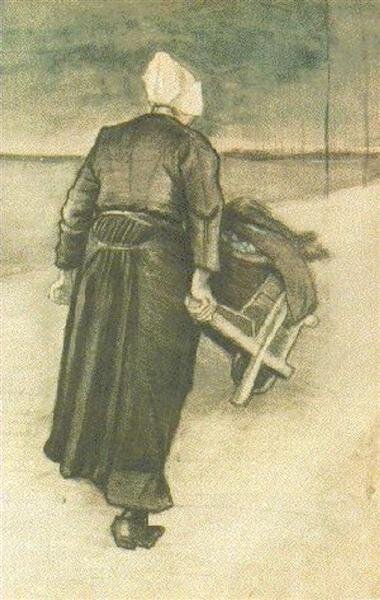

Vincent van Gogh, 1882; The Hague, Netherlands: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Georges Seurat, 1883, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By gift

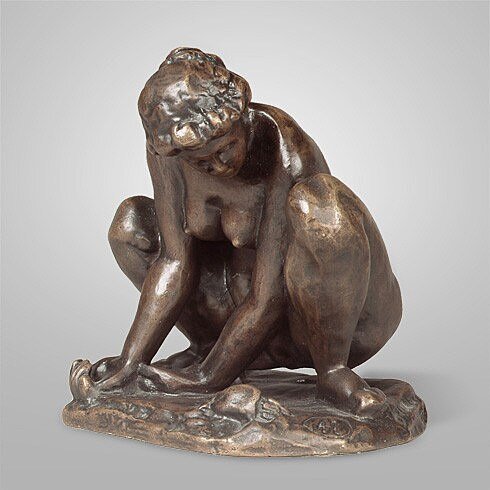

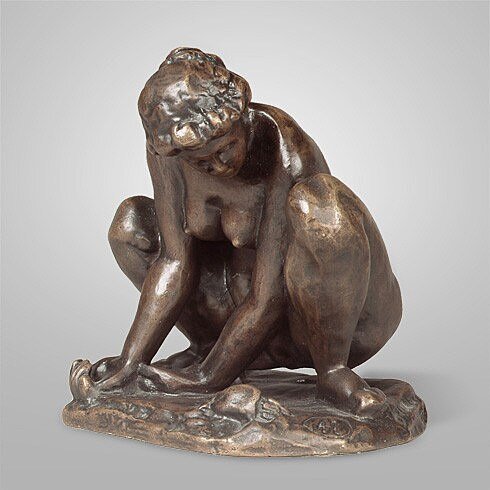

Aristide Maillol, ca. 1900–1904 (cast by 1930s), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978

MEDIUM: Bronze

DIMENSIONS: 6 x 5 3/4 x 4 3/4 inches (15.2 x 14.6 x 12.1 cm)

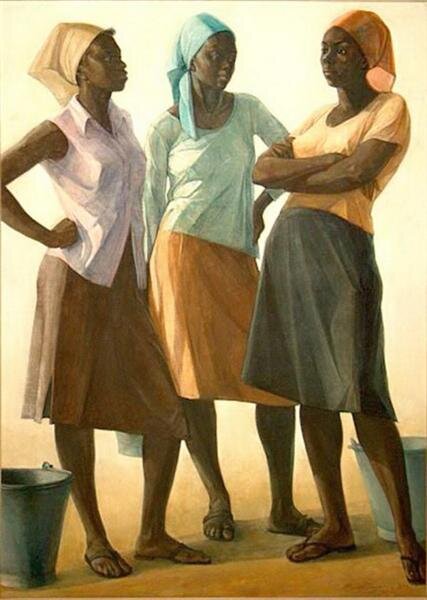

Wang Jianwei, 2014, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Collection. This film was produced on the occasion of the commission, "Wang Jianwei: Time Temple," presented at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and made possible by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation

MEDIUM: Digital color video, with sound, 55 min., 8 sec.

Pablo Picasso, 1904, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

"Images of labor abound in late-19th- and early 20th-century French art. From Jean-François Millet’s sowers and Gustave Courbet’s stone breakers to Berthe Morisot’s wet nurses and Edgar Degas’s dancers and milliners, workers were often idealized and portrayed as simple, robust souls who, because of their identification with the earth, with sustenance, and with survival, symbolized a state of blessed innocence. Perhaps no artist depicted the plight of the underclasses with greater poignancy than Picasso, who focused almost exclusively on the disenfranchised during his Blue Period (1901–04), known for its melancholy palette of predominantly blue tones and its gloomy themes. Living in relative poverty as a young, unknown artist during his early years in Paris, Picasso no doubt empathized with the laborers and beggars around him and often portrayed them with great sensitivity and pathos. Woman Ironing, painted at the end of the Blue Period in a lighter but still bleak color scheme of whites and grays, is Picasso’s quintessential image of travail and fatigue. Although rooted in the social and economic reality of turn-of-the-century Paris, the artist’s expressionistic treatment of his subject—he endowed her with attenuated proportions and angular contours—reveals a distinct stylistic debt to the delicate, elongated forms of El Greco. Never simply a chronicler of empirical facts, Picasso here imbued his subject with a poetic, almost spiritual presence, making her a metaphor for the misfortunes of the working poor.

Picasso’s attention soon shifted from the creation of social and quasi-religious allegories to an investigation of space, volume, and perception, culminating in the invention of Cubism. His portrait Fernande with a Black Mantilla is a transitional work. Still somewhat expressionistic and romantic, with its subdued tonality and lively brushstrokes, the picture depicts his mistress Fernande Olivier wearing a mantilla, which perhaps symbolizes the artist’s Spanish origins. The iconic stylization of her face and its abbreviated features, however, foretell Picasso’s increasing interest in the abstract qualities and solidity of Iberian sculpture, which would profoundly influence his subsequent works. Though naturalistically delineated, the painting presages his imminent experiments with abstraction." — Nancy Spector