Medusa — Today

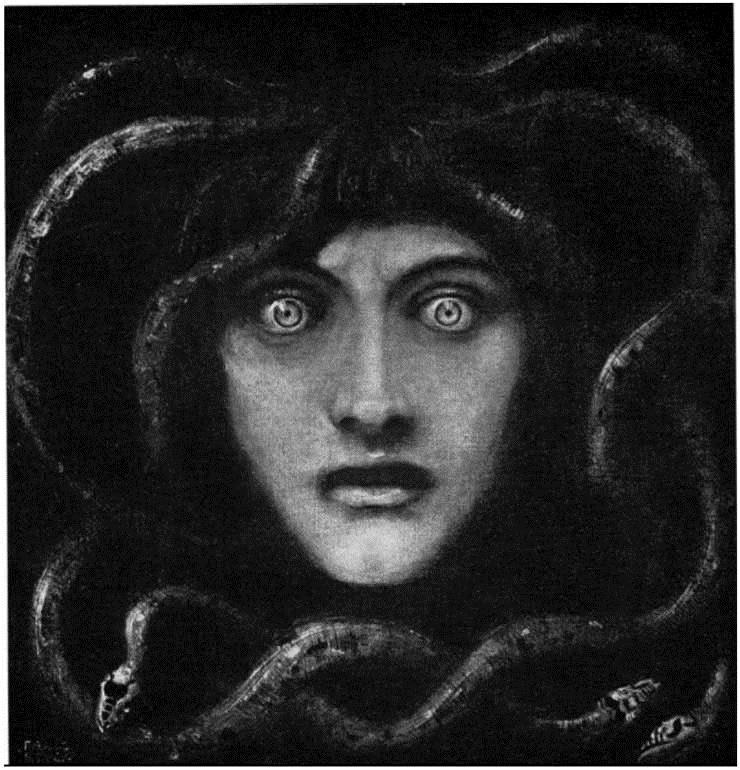

Medusa, Caravaggio, 1597, Uffizi, Florence

who is medusa?

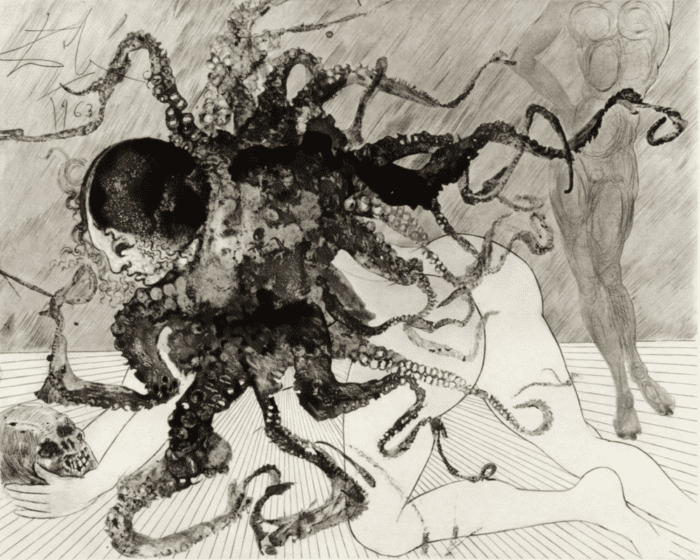

The archetypal “angry woman”, Medusa has been adopted as a symbol of female rage, and the personification of female fury.

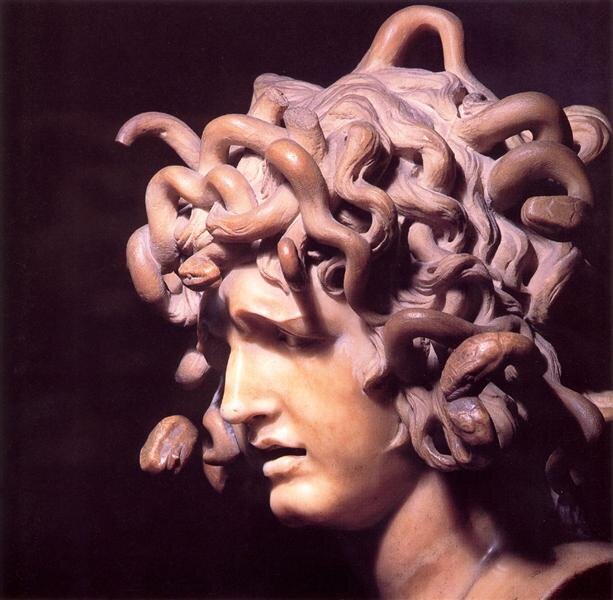

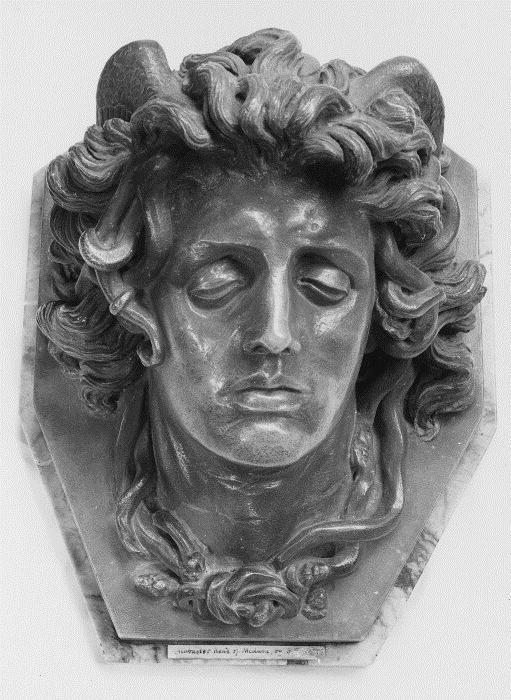

Today Medusa is largely known as a hideous female monster with snakes for hair whose fury and frightful eyes will turn viewers to stone if they so much as glance at her. Medusa has been depicted as either a Gorgon monster or a beautiful woman, who was raped (or sexually active); then blamed for being raped (or for engaging in sex); then transformed into a raging monster and subsequently beheaded.

The face of Medusa appears in paintings and sculptures throughout history; in literature, film and theatre; on boats and buildings; on housewares; and even as a logo by the fashion company Versace.

The many stories of Medusa

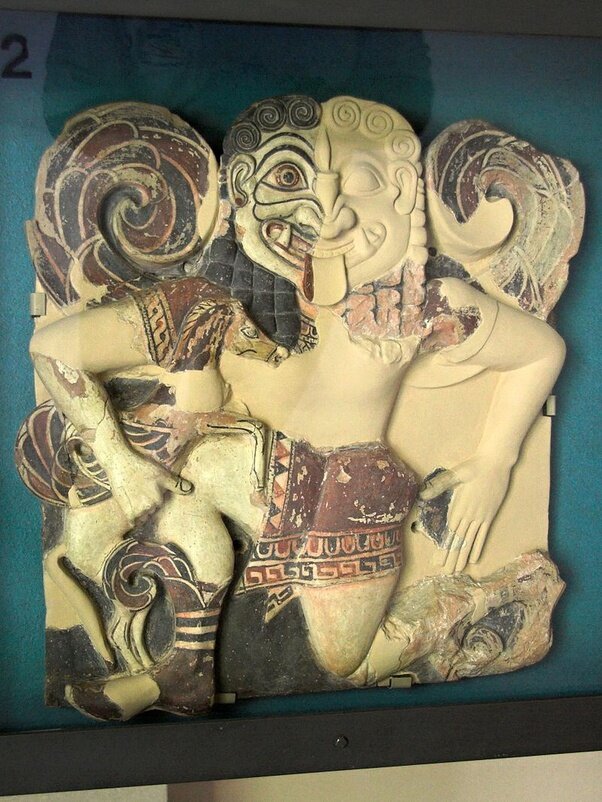

The Gorgon was a protective deity from the ancient world. A Gorgon wore a belt of serpents that intertwined as a clasp. This appears to be the origins of the caduceus, which appeared as a symbol of God Ningishzida, c 2100 BCE.

An archaic Gorgon (circa 580 BC), as depicted on a pediment from the temple of Artemis in Corfu, Archaeological Museum of Corfu

The Caduceus, symbol of God Ningishzida, on the libation vase of Sumerian ruler Gudea, circa 2100 BCE.

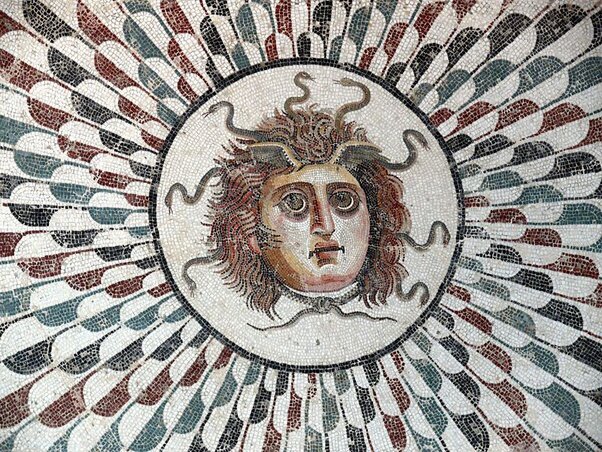

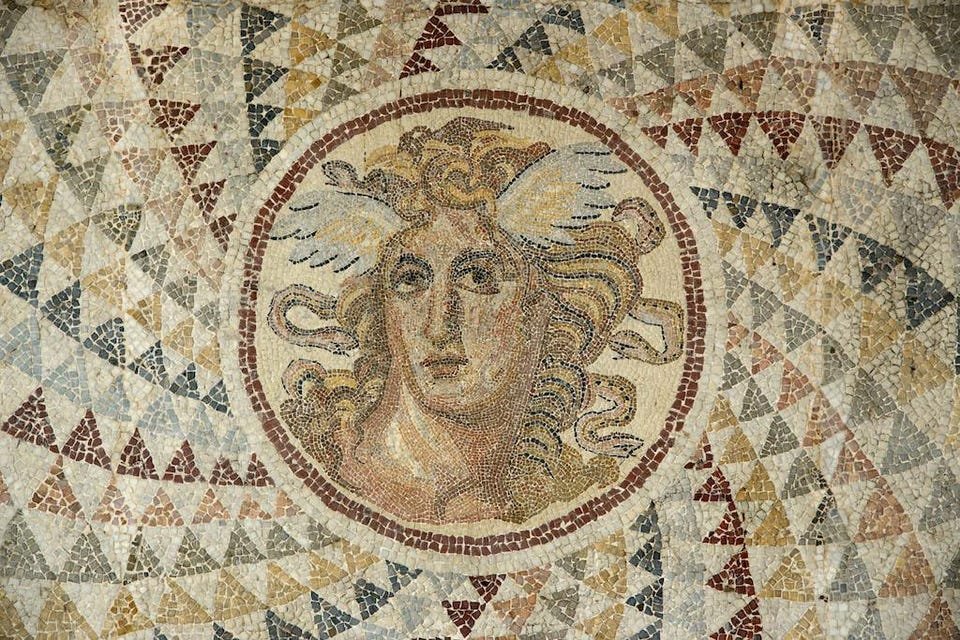

The power of a Gorgon was so strong that one would be turned to stone upon daring to gaze at her. Such images were therefore used for protection and put upon a range of items, including armour, shields, temples and wine vessels.

Detail from Alexander and Bucephalus - Battle of Issus mosaic - Museo Archeologico Nazionale - Naples. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Some suggest Medusa’s origins may be rooted in the Egyptian Cobra Goddess Wadjet or the Minoan Snake Goddess.

The oldest existing version of the story of Medusa comes from the poem Theogonia, composed circa the eighth century BCE by the Greek poet Hesiodos of Askre. Here, Hesiodos mentions that Medusa was the only mortal of three sisters, daughters of the ancient marine deities Phorcys and Ceto, chthonic monsters from the archaic world. In this version she is born a Gorgon with the ability to turn people to stone at a glance. She may also, according to some depictions, have had the body of a horse.

Hesiodos writes: “With her lay the Dark-haired One [i.e., Neptune/Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers.” Since Hesiodos makes no mention of this being a rape, we may understand that she was a willing partner in sexual activity. She was, however, still cursed and punished as a result.

In 8 AD the Roman poet Ovid wrote a narrative poem entitled The Metamorphoses (Latin: Metamorphōseōn librī: "Books of Transformations") comprising 11,995 lines, 15 books and over 250 myths, which chronicled the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar.

In Ovid’s version, Medusa was once a beautiful young maiden, the only mortal of three sisters (Medusa, Stheno and Euryale) known as the Gorgons. These sisters were also sisters of the Graeae: Deino, Pemphredo and Enyo — old women, grey ones, grey witches — who shared one eye and one tooth between them.

Being mortal, Medusa was also distinguished from them by the fact that she alone was born with a beautiful face. Ovid especially praises the glory of her hair, “most wonderful of all her charms.”

Medusa was one of the sacred priestesses serving in the Temple of Athena. Some say she had many suitors but had chosen not to marry in order to devote herself to her work. Medusa was lovely, and she knew it. Some suggested that her beauty rivalled that of Athena, but that soon changed.

One day her beauty caught the eye of the sea god Poseidon, who becomes enamoured with the lovely girl. Determined to have her at any cost, he rapes her in the sacred temple of Athena.

Furious at the desecration of her temple, Athena transforms Medusa into a monster with a face so hideous and a gaze so piercing that the mere sight of her is sufficient to turn a man to stone. Medusa’s enchanting hair is transformed into a coil of writing serpents; and she is banished to a remote and foreign land.

Soon after this, Polydectes, the king of Seriphos, sends Perseus on a quest to bring back the head of Medusa. (The king fully expects and hopes that Perseus will be unsuccessful because he wants to marry Perseus’ mother, Danaë, and requires her son be otherwise occupied.)

Perseus and the Graeae by Edward Burne-Jones (1892), image courtesy of Wikipedia

Aided by Hermes and Athena, Perseus pressed the Graeae, sisters of the Gorgons, into helping him by seizing the one eye and one tooth that the sisters shared and not returning them until they divulged Medusa’s whereabouts, and provided him with winged sandals (which enabled him to fly), the cap of Hades (which conferred invisibility), a curved sword, or sickle, to decapitate Medusa, and a bag in which to conceal the head.

Perseus Returning the Eye of the Graii, image courtesy of Wikipedia

Perseus finally reaches the fabled land of the Gorgons, located either in the far west, beyond the outer Ocean, or in the midst of it, on the rocky island of Sarpedon.

Perseus creeps up on Medusa while she is asleep. Then — using the reflection in Athena’s bronze shield as a guide so as to not look directly at Medusa and be turned into stone — Perseus decapitates Medusa with his sickle.

At the time of her death Medusa was pregnant by Poseidon. The assassination of Medusa releases her two unborn children Chrysaor and Pegasus (the winged horse) from her severed neck. The resulting noise awakens the Gorgon sisters who endeavour to avenge Medusa’s death but they are unsuccessful because Perseus is wearing Hades’ Cap of Invisibility and Hermes’ winged sandals. Returning to their cave the sisters mourn their fallen sister. Hearing their gloomy lament it is said that Athena modelled the music of the double pipe, the aulos, after the sound.

On the way back to Seriphos, flying across northwest Africa, Perseus stopps briefly in Ethiopia. There, he rescues and weds his future wife, the lovely princess Andromeda who he found naked and chained to a rock on the shore. (Save that for another story). The corals of the Red Sea were said to have been formed as Medusa's blood spilled onto seaweed when Perseus laid down her severed head beside the shore — attending to Andromeda’s rescue.

Bronze ornament from a chariot pole, 1st-2nd century A.D. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Later as Perseus flies across the sands of Libya, with Medusa’s putrefying head clutched in his hands, the falling drops of her blood create a race of poisonous vipers of the Sahara; and also spawn the Amphisbaena (a horned dragon-like creature with a snake-headed tail). And that is why that, to this day, Libya abounds with serpents.

Perseus then flew to Seriphos, where his mother was being forced into marriage with the king, Polydectes. Perseus used Medusa’s head to turn him and various other vicious islanders into stone — which explains why the island became famous for its many rocks.

Perseus then gave Medusa's head to Athena, who placed it on her shield, known as the Aegis.

Athena also collected some of the remaining blood and gives most of it to Asclepius, who used the blood from Medusa’s left side to take people’s lives and the blood from her right side to raise people from the dead. The rest of Medusa’s blood – a vial containing two drops – Athena gave to her adopted son, Erichthonius; Euripides says that one of the drops was a cure-all, and the other one a deadly poison. She also put aside, in a bronze jar, a lock of Medusa’s hair for Heracles, who subsequently gave it to Cepheus’ daughter, Sterope, to use to protect her hometown Tegea. Although the lock of hair lacked the power of Medusa’s gaze, it could still cast terror into any enemy unfortunate enough to behold it, accidentally or otherwise.

“As Mary Beard points out in her book Women & Power: A Manifesto: Medusa has become part of the mythological invective often hurled at women running for and achieving political office: Angela Merkel, Theresa May, Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren—to name just a few. Although design houses like Versace (and some might say even comedian Kathy Griffin) have tried to reclaim the myth of Medusa for women, it has largely not been effective. Medusa remains the symbol of the quintessential nasty woman that must be vanquished in order to restore the balance of power.”

For additional interesting reading see: rape victim turned into a monster

is there More to the story of Medusa?

When considered within an historical context, however, one wonders if the roots of the story might go much deeper.

Greek historian Herodotos of Halikarnassos (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) wrote in Histories 2.91 that Medusa and her sisters lived in the land of Libya, which, for the ancient Greeks, meant the whole part of North Africa west of Egypt.

Some suggest that the origins of the character Medusa may be rooted in the Egyptian Cobra Goddess Wadjet. Depicted as a snake-headed woman or a cobra she was associated with the land as matron and protector of Egypt; of kings and of women in childbirth. As the nurse of the infant God Horus, Wadjet was closely associated with the Eye of Ra.

Wedjat Eye, Egyptian Amulet, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

The Eye of Ra

The word “Egypt” comes from the Greek word for “Black”, referring to the Black Nile, but possibly also referring to the people. Her serpentine hair may have been dreadlocs.

She may also have derived from the Minoan Snake Goddess.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wadjet

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perseus

- https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Creatures/Medusa/medusa.html

- http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth200/Body/snake_goddess.html

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/votary.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snake_worship

- https://commons.wikimedia.org

- https://guts4garters.wordpress.com/2009/05/25/the-angry-woman-feminism-medussa/

- https://talesoftimesforgotten.com/2020/10/10/where-does-the-myth-of-medusa-come-from/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorgon

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graeae

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Burne-Jones

- Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe, Marija Gimbutas, 1991

- New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd., New York, 1959

- Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood, Merlin Stone, Beacon Press, Boston, 1984

- When God Was A Woman, Merlin Stone, Harvest Edition, 1976

- The Language of the Goddess, Marija Gimbutas, HarperRow publishers, San Francisco, 1989

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Egyptian_hypothesis

- http://arthistoryresources.net/snakegoddess/

- https://rbgstreetscholar.wordpress.com/2007/11/24/black-egyptians-the-original-settlers-of-kemet/

- https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/collections/arts-of-one-world

- https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-depictions-medusa-way-society-views-powerful-women

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/drsarahbond/2017/11/23/rehabilitating-medusa-powerful-women-sexism-and-reading-mary-beards-new-book/#6d3639684c43